Simon Gallacher is a freelance evaluator and education and research policy adviser. In a blog first published exclusively on STEM Community, he's looked in depth at the issue of historical teacher recruitment...

The latest monthly Initial Teacher Training recruitment data was released recently. With a bit of tweaking, this can be matched up to the ITT targets for the corresponding year. It doesn’t look good, with only four secondary subjects (Drama, History, Physical Education and Classics) currently at or above the recruitment target. If all conditional offers and pending decisions go the right way, then Art and Design, Mathematics (yes!), and Chemistry may join them. Physics, Design and Technology, and Computing are around 30% of the ITT target. But is this just the way things are, or are we experiencing what the School Teachers’ Review Body (STRB) suggest are ‘persistent’ and ‘severe’ supply issues?

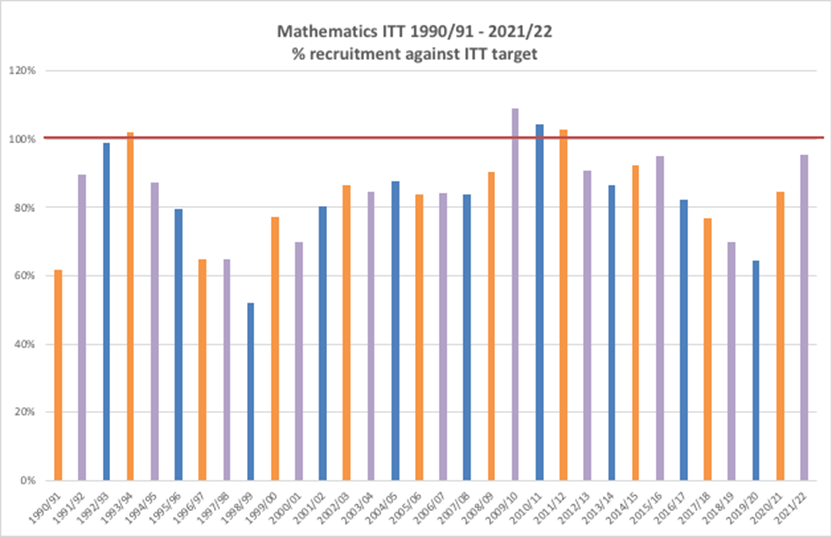

I looked at data on ITT targets and recruitment for as far back as I can (just over 30 years) to get a sense of the bigger picture. I've also been looking at what the STRB has said about STEM subjects over a similar period and tried to ascertain whether, after over nine years of ITT targets being missed in most subjects, the ‘Golden Days’ ever existed…or whether it’s all cyclical.

There are challenges in looking at the data over a long period: subject designations change and morph. For example, since 2011/12, there have been separate targets for Biology, Chemistry and Physics – before that, there was simply ‘Science’. Between 1990/91 and 2010/11, the recruitment target for Science was met (or 99% met) on six occasions, which may give cause for celebration. However, there were imbalances in the supply of the different subject specialisms (particularly for schools in disadvantaged areas), so a subject focus has helped to train attention on this area.

Computing (and ICT) was once combined with Mathematics targets (1991/92-1993/4) and subsequently with Design and Technology before ‘breaking free’ in 2008/09. Only Mathematics (in the suite of STEM subjects) gives an easy and illustrative 32-year perspective on recruitment/versus targets.

The decline in Mathematics ITT was arrested and reversed in 1999/00 after five years of decline - possibly abetted by uncertain economic times in the early 1990s. However, the period of decline from 2011/12 seems much more chronic, although there are some green shoots. For subjects like Chemistry, Computing, Design and Technology, Physics (and Modern Languages), the picture is much less good even where the incentives and attractions are similar to those for ITT in other priority subjects.

It's worth recalling that keeping ITT supplied with graduates is a very demanding task. As far back as 2003, the STRB noted that the demands of postgraduate ITT could require 10% of all graduates to become teachers (and 40% of Mathematics graduates). More recently, it was estimated that 20% of maths and physics graduates will be required to become teachers to meet recruitment targets. Such a demand requires continuous activity to make teaching an attractive and attainable career prospect.

Was there something different about the 2000s? Arguably, the routes to becoming a teacher were less complex and confusing. There were also considerable, evidence-led, and sustained policy developments related to STEM subjects. The (first) mathematics review of Professor Sir Adrian Smith and the Roberts’ review was closely followed by an ambitious ten-year (2004-2014) science and innovation investment framework. This gave added momentum to the strategic efforts to improve and stabilise the supply of STEM teachers. This was also a period where bursaries were introduced, Golden Hellos (financial incentives linked to retention) appeared, and the repayment of student loans (2002) for new entrants to STEM ITT (an idea that resurfaced in 2018) was trialled. This, and efforts to change the working conditions in schools and the perception of teaching as a profession may also have contributed to teaching becoming the second most popular choice of career* for undergraduate students. It would be interesting to know where it ranked now.

Looking back through the 30-plus STRB reports, there are very few years without a mention of challenges concerning STEM ITT and teacher retention - and those references do appear to be more regular and prominent in recent years (with even the National Audit Office contributing its voice). However, there are also periods where steady and deliberate improvements have been made. Initiatives were tried (but not always tested – and that is a continuing problem), but there is enough of an understanding of what is effective in driving a supply of teachers to help navigate a way out of the current and worrying decline. This will undoubtedly have a greater impact on schools in disadvantaged communities, with the knock-on effects of limiting opportunities and restricting the future diversity of the STEM workforce. Perhaps the pandemic-induced moves to better and more effective online teaching and learning may also play a part in managing the demand for teachers, with high quality teachers in priority subjects operating across a range of schools. Still, whatever happens, it feels hard to avoid the need to reset the way we plan and manage the supply of well-prepared and qualified teachers for all 22,047 state schools in England.