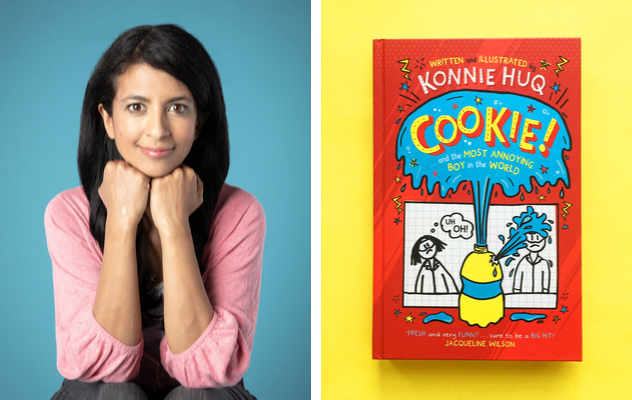

STEM education campaigner and former Blue Peter presenter Konnie Huq explains the motivation behind her new book and its central character, a science-mad nine-year-old girl

I’ve done a lot of STEM Learning initiatives, with the British Science Association and the Institution of Engineering and Technology, among others, and I’m aware of what a dearth there is of young people from the UK going into STEM professions. Boys as well as girls, although it’s worse for girls.

I also do a lot of BAME [black and minority ethnic] work, because there are pretty abysmal figures for minorities in STEM too. What really struck me is that when my parents came over to the UK from Bangladesh in the 60s, for them and all their peers, culturally, the revered professions to go into were engineering, being a doctor, being an accountant – STEM was the epitome of having made it.

Over my years on Blue Peter, I’d ask children what they wanted to be when they grew up, and the answer was often “to be famous”. But they didn’t know what they wanted to be famous for. STEM isn’t seen as a revered path or as being glamorous or desirable in our society, it gets a bad PR.

I believe the only way to change society is through children. Children are born as a blank canvas and all they know is what we put on to them. If they think it’s great to be rich and powerful and have loads of followers on Instagram or whatever. That’s what society is teaching them. If they grow up in a society that tells them it’s really good to be an engineer, that’s what they’ll think.

Start science young

So we need to get kids enthused about science when they’re young, and the problem is that I don’t think lots of kids are really exposed to science until secondary school, and that’s too late; it’s like a foreign language, it’s already this alien thing.

The younger someone is introduced to something, and the more they’re exposed to it, the earlier it will be absorbed. It’s about being aware of it; it doesn’t matter if you don’t fully understand concepts. Of course we’re not expecting them to understand the electromagnetic spectrum at the age of four, but the more something is in their consciousness, the more chance we’ll have.

I think it’s all up for grabs for kids in primary school. As a child I didn’t see myself represented on TV or in books, so I didn’t think certain fields were open to me. If you had said to me at primary age that I’d be on television, I’d have said that people like me aren’t on telly. I remember hearing a woman’s voice on the radio, and consciously thinking “I didn’t know women could be on the radio.”

Our perceptions are made by what we’re aware of; the more I hear a woman on the radio, the more we have this diversity and free-flow of ‘anyone can do anything’, the more that is the norm. It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Arts and science: a brilliant marriage

Growing up, I often remember people asking “are you an arts person or a science person?” and I would think “Well, I’m both really”, because I did like maths and I did science A levels and I was going to be an engineer, but I also loved performing and drama.

I think more and more, people are realising the two go hand in hand; you can’t have one without the other. STEM activity involving innovation and tech includes creativity and branding. As we go forward with new developments in tech, there are so many opportunities to do both arts and science.

In my book, the main character, Cookie, is a nine-year-old girl. She’s got a very creative mind, but she’s also quite logical, practical and ‘sciencey’ too. One of my all-time heroes is Ada Lovelace; she is the epitome of how arts and science can be a brilliant marriage.

Charles Babbage saw computers as number crunchers. Bring a woman to the equation and you often get a new light shone on a problem or a new way of looking at something. Ada Lovelace saw the capacity computers had for making music, making art. I think women approach things differently. Look at all the people in Silicon Valley – they’re all highly creative and highly technical.

Put it in context

You need science to be relatable and often to children it isn’t, it’s not put into context. I remember not understanding the point of maths as a child, because we had calculators! I didn’t get the practical applications.

I remember this turning point of understanding algebra and differentiation and realising that enables you to work out the current going through a wire or the average speed of a car. These different unknowns that if you can work them out, you can make buildings that don’t fall down, and planes that fly. When children are struck like that with something at primary school that is interesting or exciting, they take that with them for life.

All these things are done through calculations and that’s what has led to our society being so progressive. As Cookie says in the book, without science we’d be living in caves with simple tools.

Konnie Huq’s new book, Cookie and the Most Annoying Boy in the World is available from Amazon and signed copies are available from Waterstones. You can follow Konnie on Twitter at @Konnie_Huq.